Friends and family, near and far —

I sure appreciate people who still send greeting cards; it’s a rarity these days. For now, this is the best I can do.

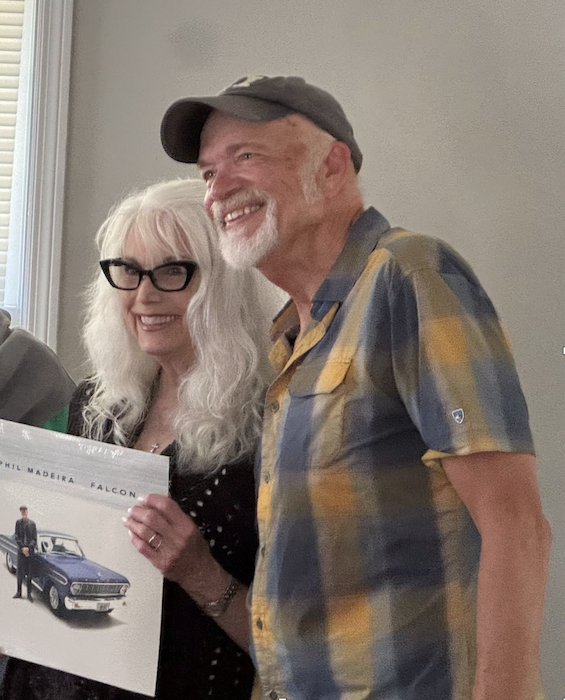

2025 was yet another year in which I continued the creative streak I’ve been on for about a decade. I released a live record and a studio record called “Falcon”. I’m pleased with the work, and with those folks who keep supporting my annual offerings. Last year, I started the one I’ll release in 2026 — mostly 70s flavored country, with guests like Vince Gill and Phil Keaggy. Fun!

We didn’t do a ton of Emmylou dates in 2025, but we’re gearing up for quite a few European dates this coming year, and that makes me real happy. Meanwhile, Red Dirt Boys recorded another record, and played locally at Brown’s Diner quite often for tips, burgers, and good times.

The coolest gig of the year was in San Francisco right before our annual appearance at Hardly Strictly Festival — A tribute show to my pal and boss of nearly 2 decades — Emmylou Harris, which featured many fantastic artists from Buddy Miller to Shawn Colvin, to Joan Baez (better than ever!), and (particularly thrilling to me) Bonnie Raitt. I don’t get nervous about these things, but the thought of playing with Bonnie honestly intimidated me! It was a great night.

I ended the year by going out on Sixpence None The Richer’s “O Night Divine” Christmas tour, playing keys, Lap Steel, and Electric Guitar — and it was fun. The big deal on that tour was playing NPR’s Tiny Desk in DC — you can find it on YouTube. It was great to perform with these good friends, especially my fellow sideman / hiker Steve Hindalong.

Christmas Day found me with Kate (35) and Maddy (33) at Elinor’s (still 29) for our traditional Swedish meal, which is what my mother always prepared for as long as I can remember. I’m glad that it means something to our kids to keep the tradition.

Jenny couldn’t attend, and we missed her, but she has family in nearby Clarksville that she rarely sees, so that’s where she was.

Elinor is happily retired and cancer-free. Hallelujah!

Kate is a barista for Starbucks, and Maddy works at a vegan deli — they are both exceedingly creative, musical, artistic, and generous souls, and I’m happy to spend time with them. We enjoy gathering fairly often — all 5 of us — for a meal and a visit.

Jenny is solid gold, and a bright light. She brings joy into the lives of everyone whom she meets, and likes to think of herself as a bridge builder. That seems like a hard job these days, when our nation is as divided as it is. We hope for positive change to come sooner than later, as 2025 was (in my opinion) a bad year for America. The two of us will head to Ireland in April to do my Mercyland In Ireland songwriter workshop in cahoots with my mate Sammy Horner.

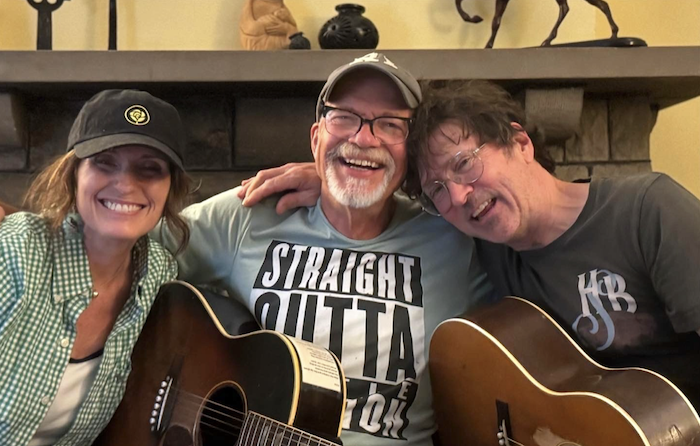

Cindy Morgan, me, Will Kimbrough at Summer Mercyland

The US Mercyland was a winner this year in both the summer and fall sessions, and I’m glad I keep at the work of helping people express themselves through music and lyrics. What’s crazy is that some of these songs wind up on records I’m involved with, including 2 Mercyland songs on the Falcon record.

I could probably fill a book about 2025, but then I’d have to charge you for it. Speaking of that, I am close to finishing the book I began a few years ago. Here’s hoping.

The older I get (73), the more I want to put goodwill into the world. There’s a time for protest and a time for encouragement, kind words and stern, but whatever my lyrics are, I hope my goal of sending light into the world is met, if in even the smallest glimmer.

It’s Christmas in America, and the divine Birthday Boy wouldn’t be allowed across our borders if he showed up in 2025. If you’re looking for Jesus, you’ll find his face among the poor, the outcast, the immigrant, and the deported. The best way to welcome him into your heart is to welcome them.

Peace and love,

Phil Madeira